|

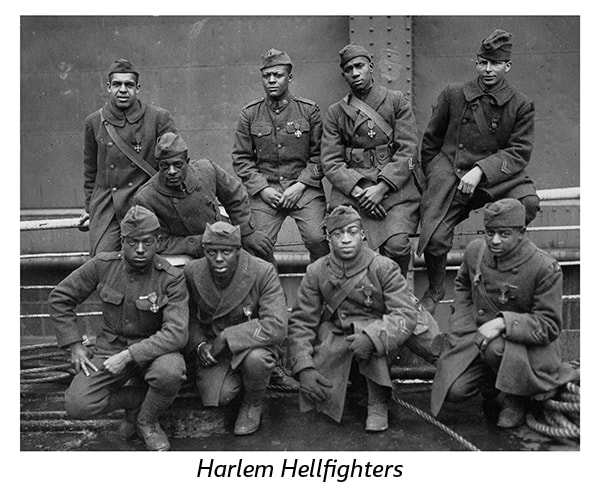

Content compiled by The Washington State Department of Veterans Affairs (WDVA). Despite their constant presence in even the earliest iterations of the nation’s armed forces, the service of a Black individual has only recently been measured equally against that of a white servicemember. Though more visceral and violent acts of discrimination may have greatly diminished in our modern era, there’s still advancement to be made. Around 9,000 Black soldiers served during the Revolutionary War, many of whom were slaves enticed to enlist with the promise of freedom, only to find themselves forced back into bondage after the close of the conflict. During the Civil War, the Black servicemen of the Union were treated in different wards than the white soldiers. These wards were poorly staffed and undersupplied, leading to many Black soldiers dying from wounds that white soldiers would survive. The Confederate Army used both free and enslaved Black people for labor and menial tasks but refused to enlist them as combat infantry. Black veterans faced the same, and sometimes worse, racism upon returning from their enlistment during the early 20th century. Mississippi Senator James Vardaman said in 1917 that once a Black soldier saw himself as an American hero, it was “a short step to the conclusion that his political rights must be respected” and would “inevitably lead to disaster.” Charles Lewis was lynched while still in uniform in December 1918 after being accused of robbery and assault. A Louisiana restaurant owner shot and wounded four Black soldiers in 1944, claiming they “attempted to take over his place.” Joe Nathan Roberts, a Navy veteran, was abducted from his family’s home and shot to death in 1947 after refusing to call a group of white men “sir.” Isaiah Nixon, a Black veteran, was shot and killed outside his home and in front of his wife and six children in 1948 because he voted in a local primary election. These veterans’ service to their country meant little to the violent bigots of the population who shared their hometowns.

Some veterans had to fight for their benefits after receiving a “blue ticket” discharge in the 1940s. These administrative discharges were largely used to ouster homosexual service people and Black individuals. More than 20% of all “blue tickets” were issued to Black soldiers, though they comprised only 6.5% of the Army. The VA denied benefits of the G.I. Bill to those with these discharges, and many found it difficult to secure employment after separation. These discharges were halted after an outcry by the press and an investigation by the House Committee on Military Affairs in 1947. Executive Order 9981, which in 1948 officially desegregated the armed forces, did much toward the bureaucratic correction of longstanding inequalities. While conditions have improved for veterans in today’s world, there are still changes to be made. According to HUD’s 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, Black veterans make up one-third of homeless veterans, while they comprise only 12% of the overall veteran population. The VA continues to research the disparity between poorer health and reduced services experienced by Black veterans and other minority groups, and those of white veterans. Currently, there are around 230,000 Black active duty Department of Defense personnel, or about 20% of the DoD’s total force. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorSOur blog includes but is not limited to events, insights, and highlights to augment basic education. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed